Overactive Bladder

Most people are familiar with that occasional, urgent need to urinate—the feeling that there’s little time to spare and you need a bathroom ASAP.

But imagine having that feeling constantly. That’s the situation for people with overactive bladder (OAB). They may need to plan their day around bathroom availability, watching for the nearest restroom sign when they are away from home.

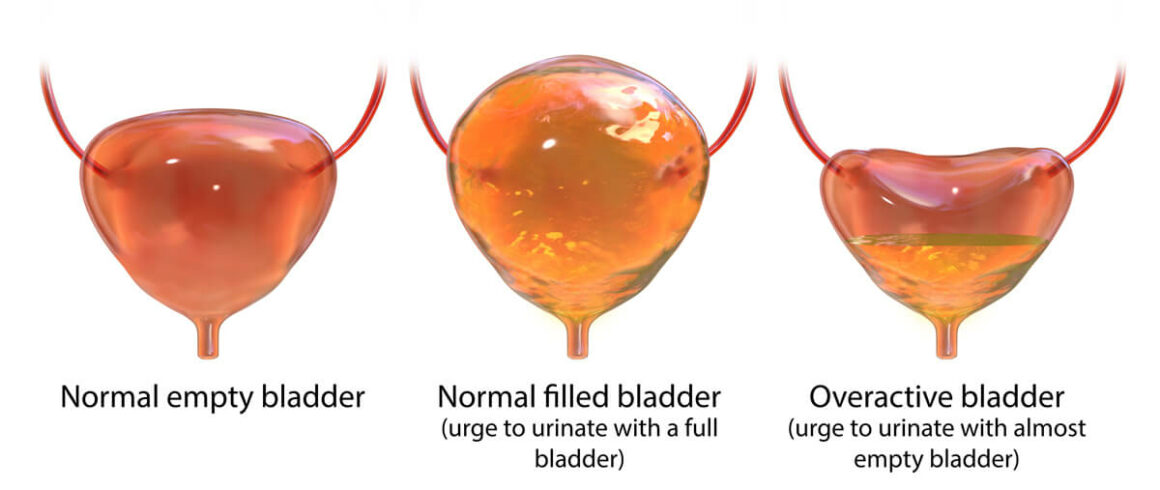

Overactive bladder is not a specific disease, but a group of symptoms:

- An almost-constant, urgent need to urinate, even after the bladder has been emptied.

- Urge incontinence. Some people with OAB leak urine, from a few drops to the entire contents of the bladder.

- Waking up more than once during the night to urinate (nocturia).

- Needing to urinate frequently, sometimes more than 8 times in 24 hours.

OAB is sometimes called “spastic bladder” or “irritable bladder.”

OAB can affect a person’s emotional health, too. Many people feel anxious about urine leak accidents or embarrassed about needing the bathroom so frequently. They may shy away from socializing, feel isolated, and become depressed.

About 33 million people in the United States have OAB, according to the National Association for Continence (NAFC). It’s particularly common in older people, women who have gone through menopause, and men with prostate issues. People with neurological conditions like stroke or multiple sclerosis are also more likely to have OAB.

OAB is sometimes called “spastic bladder” or “irritable bladder.”

Some people think that poor bladder control is just something they have to live with, especially as they get older. But that’s not the case at all.

The good news is that OAB is treatable. With time and patience, OAB symptoms can greatly improve.

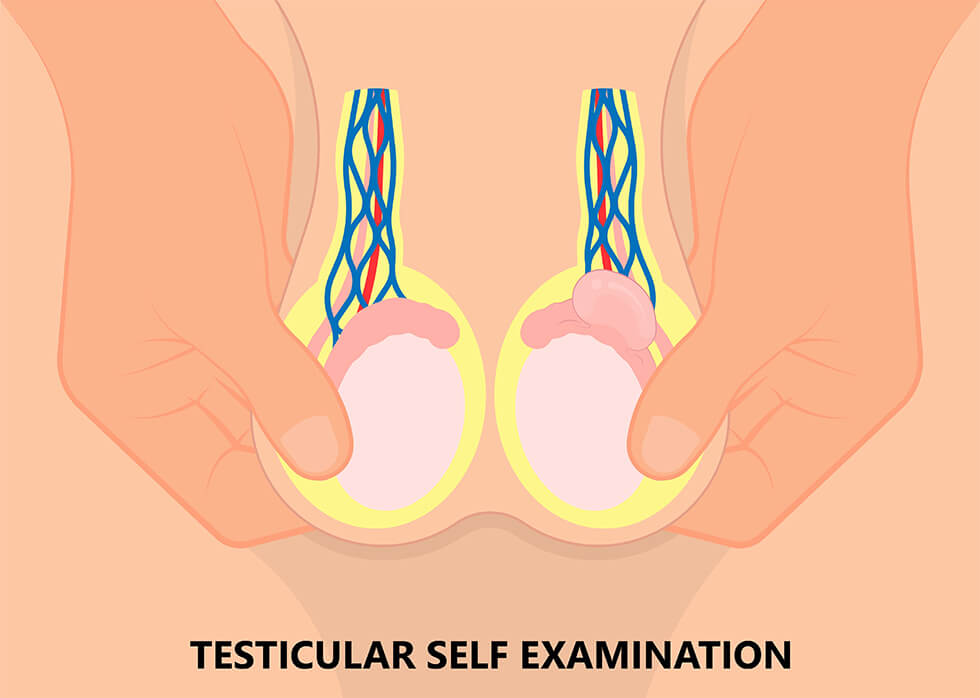

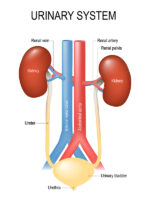

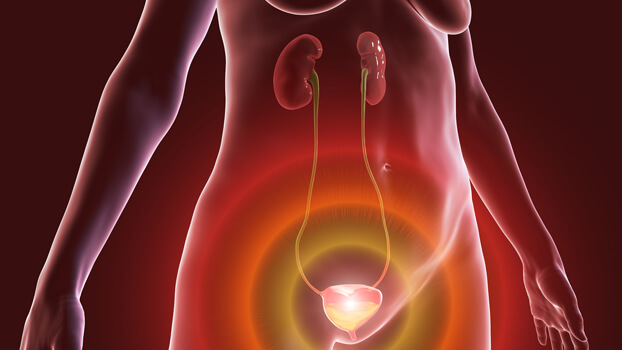

How does the urinary system work?

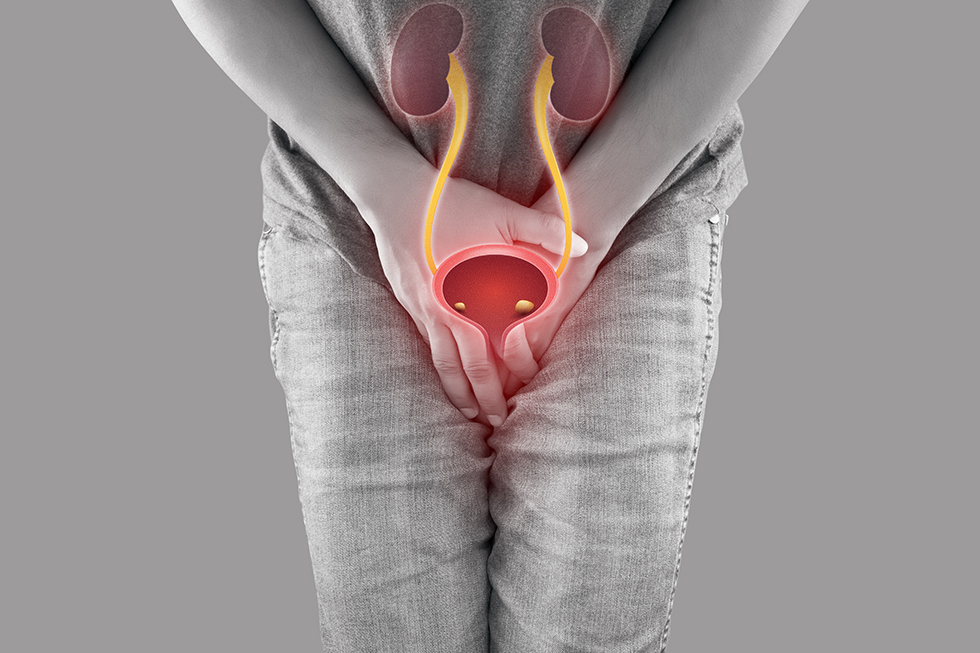

Typically, a person has two kidneys. These are the organs that make urine. Extending from each kidney is a ureter—a tube that connects to the bladder. Once produced, urine flows from the kidneys, through the ureters, to the bladder, where it is stored until a person urinates. On average, the bladder can hold about 2 cups (16 ounces) of urine before it needs to be emptied.

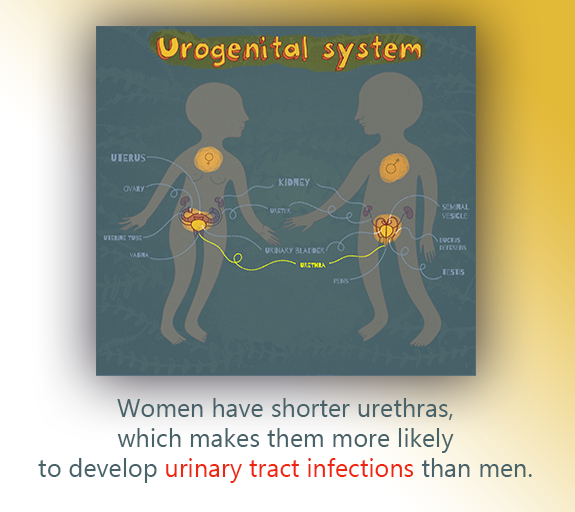

At that time, the nerves in the bladder send a message to the brain, signaling the need for emptying. When it’s time to urinate, the brain sends a message to open the bladder’s sphincter muscle, which acts as a valve. Once open, urine flows from the bladder out of the body through a tube called the urethra.

With OAB, communication between the brain and bladder muscles are disrupted.

What causes overactive bladder?

With OAB, communication between the brain and bladder muscles are disrupted. As a result, a person will have that “I need go right now” feeling more urgently and more often. It also happens when the bladder isn’t full.

How is overactive bladder diagnosed?

Lots of people are reluctant to discuss urinary symptoms with a healthcare provider because it can be awkward and embarrassing to talk about bathroom issues. Hiding the problem doesn’t help and leads to unnecessary suffering.

When a person talks about urinary symptoms like those related to OAB with a healthcare provider, the provider will ask about the patient’s overall health and the medications currently being taken. They’ll also want to know about any past illnesses or surgeries.

They’ll also want more specific information about the urinary symptoms. For this reason, patients might be asked to keep a bladder diary for a few days.

A bladder diary is a place to jot down symptoms and urination patterns. It can be as simple as a spiral notebook or handwritten chart. Or it can be high-tech, like a smartphone app. Whichever method is chosen, these questions can reveal patterns:

- How often is a patient urinating? What time of day?

- What is the patient doing when he/she feels the need to urinate?

- How strong is the urge to urinate?

- How much urine is being released?

- Are there any accidental urine leaks?

- What is the patient eating and drinking? How much?

- How do the circumstances affect the patient’s daily routine?

Urologists usually ask patients to keep a bladder diary for at least 3 days. Those days don’t have to be consecutive, but they should be 3 typical days. Patients should try to keep track of symptoms for 24 hours at a time.

In addition to the diary, doctors might ask patients to measure how much urine is released. A person might be given a special cup to use, or might use a cup from home, as long as it is known how much liquid it can hold.

When diagnosing OAB, urologists may conduct other assessments, too:

- Physical exams. The doctor might feel your abdominal organs or conduct a pelvic or rectal exam.

- Urinalysis. Lab technicians examine a urine sample under a microscope and check it for certain chemicals and substances.

- Urine culture. Specialists use a urine sample to grow bacteria in a lab. You might have a urine culture if your doctor suspects a urinary tract infection or bladder infection in addition to OAB.

- Post-void residual assessment. Using a catheter or ultrasound, the doctor checks to see how much urine remains in your bladder after you urinate. This test can provide clues about a bladder infection or blockage, which might share symptoms with OAB.

How is overactive bladder treated?

OAB can be treated in several ways. It may just be a matter of changing foods you eat and training your bladder to hold urine longer. Some people take medications to relax the bladder muscle. Others undergo certain procedures or, in rare cases, surgery. Sometimes, a combination of treatments is needed.

Lifestyle Changes

Patients might be able to adjust their daily habits to make them more bladder-friendly.

Dietary Changes

Certain foods and drinks can irritate the bladder:

- Caffeinated and alcoholic beverages. These are called diuretics, and they cause the kidneys to make more urine.

- Citrus fruits, like grapefruits, oranges, and lemons.

- Sugar and artificial sweeteners.

- Tomatoes and tomato-based foods like pasta sauce and ketchup.

- Carbonated beverages, such as soda and seltzer water.

- Spicy foods.

- Onions.

- Cranberries.

- Chocolate.

- Processed foods.

It can be hard to tell whether a specific food is triggering OAB symptoms. For this reason, an elimination diet can be helpful. With this diet, you stop consuming foods and drinks that could be triggers. Then, you gradually add them back, one by one.

For example, you might add oranges back to your diet. If your OAB symptoms worsen, then oranges are probably a trigger for you. But if you have no problems, then you can probably eat oranges with no problem.

Remember, everyone is different. A food that is an OAB trigger for one person may not trigger symptoms in another.

Some patients find that adding fiber to their diet improves OAB symptoms. Fiber may relieve constipation, which puts pressure on your bladder. Fiber is found in foods like whole grains, fruits and vegetables, and beans. An over-the-counter stool softener or laxative might be helpful, too.

Fluid Management

Your doctor can help you determine how much fluid to drink each day.

Double Voiding

Voiding is another term for urinating. Double voiding means urinating twice during the same bathroom visit. Urinate as you normally would, then wait a few seconds. Then try urinating again to empty your bladder.

Delayed Voiding

When you feel the urge to urinate, try waiting a few minutes before going to the bathroom. Over time, try increasing the waiting period. You might start with two or three minutes and gradually build up to waiting 2 or 3 hours. This process trains your bladder to wait longer between bathroom visits.

Timed Urination

This means training your bladder to urinate on a specific schedule. You might start by urinating when you wake up at 7 a.m. Then, plan bathroom visits every 2 to 4 hours, depending on what works for you.

Pelvic Floor Exercises

The pelvic floor muscle group supports your pelvic organs, including your bladder. Strengthening these muscles may improve OAB symptoms. Your doctor can teach you how to target these muscles and develop an effective exercise plan. (Kegel exercises are one example. Another is “quick flicks,” which involve quickly squeezing and releasing your pelvic floor muscles repeatedly.)

Pelvic floor physical therapy might include biofeedback. This technique uses electrodes placed on the abdomen or anal area to help patients identify and control their pelvic floor muscles.

Medications

If symptoms don’t improve with lifestyle changes, medication is usually the next step. We might recommend meds on their own or in combination with lifestyle changes. Sometimes, more than one medication is prescribed.

The most commonly used drugs for OAB are anti-muscarinics and β-adrenoceptor agonists, which can be taken by mouth or administered as a patch that you wear on your skin. These drugs relax the bladder muscle and allow the bladder to hold more urine.

These medications can have side effects, such as dry mouth, dry eyes, constipation, and blurred vision. If you experience these or any other side effects, let your healthcare provider know. Changing the dose or the type of medication might help.

Botox® Injections

If lifestyle changes and medications aren’t successful, injections of Botox® may be another option for treating OAB. Botox® can relax the detrusor muscle (found in the bladder wall) and relieve the urgent feeling. It can also help your bladder hold more urine.

Botox® therapy is given in a urologist’s office and takes about 20 minutes. After you’re given local anesthesia, the doctor inserts a hollow tube called a cystoscope through your urethra and into your bladder. The cystoscope has a camera at the end and allows the doctor to see the inside of your bladder. Botox® injections are given with a thin needle through the cystoscope.

After treatment, you might notice some blood in your urine or a burning sensation when you urinate. These side effects eventually go away. If necessary, medication can be prescribed to relieve some of the discomfort.

It may take a few days—or up to 2 weeks—to notice improvements in OAB symptoms. However, Botox® provides OAB relief for about 6 months, on average. For some people, relief lasts for up to a year. Still, the effect does diminish eventually, and repeat treatments are usually necessary.

Urinary retention—an inability to empty your bladder—can be a side effect of Botox® treatment. If this occurs, you might need to self-catheterize. This process involves inserting a flexible tube called a catheter through your urethra and into your bladder. Urine then drains from the bladder to the toilet or a collection bag. Your healthcare provider will show you how to use a catheter properly.

About 10% of patients experience allergic reactions to Botox®, which can include weakness, changes in vision, and breathing difficulties. Call your provider if these side effects occur.

Nerve Stimulation (Neuromodulation Therapy)

As noted above, OAB occurs when nerve signals between the bladder and brain don’t connect properly. Nerve stimulation uses electrical pulses to improve communication between these organs.

Nerve stimulation can be done in 2 ways:

Percutaneous tibial nerve stimulation (PTNS)

The word percutaneous means “through the skin” and tibial refers to the tibial nerve, located in the leg. With PTNS, electrical pulses are sent to your tibial nerve though an electrode placed under your skin, near your ankle. These pulses help nerve signals travel properly.

PTNS is typically administered in 12 weekly sessions, but some people need more sessions. Each session lasts for about 30 minutes. Side effects are rare, but some people experience mild pain, tingling sensations, bruises, or bleeding.

Sacral neuromodulation (SNS)

SNS involves the sacral nerve, which transmits messages among the brain, spinal cord, and bladder. This procedure is considered surgery and is completed in 2 parts.

The first step is a testing phase. After you’ve been given anesthesia, the surgeon places a small electrical wire beneath the skin in your lower back. This wire is connected to a special device called a stimulator, which triggers the electrical pulses. (Sometimes it is called a pacemaker.) This device runs on batteries and may be worn outside the body, but you can also hold it in your hand. For a few weeks, you and your doctor will test the process and see how it affects your OAB symptoms.

If the test is successful, you’ll have a second procedure to place a permanent stimulator device near the sacral nerve. You will still have a programmer to adjust the stimulation. You will also have follow-up appointments to make sure everything is running smoothly.

Possible complications of SNS surgery include pain, infection, bleeding, and wire movement. Let your doctor know if you have any discomfort.

The implanted, permanent device has a battery, which might need replacing (via surgery) in a few years.

Other Surgical Approaches: Bladder Reconstruction and Urinary Diversion

Severe cases of OAB may require bladder reconstruction or urinary diversion. However, these situations are rare.

- Augmentation cystoplasty is surgery that makes the bladder larger, creating more space to store urine.

- Urinary diversion creates a new path for urine to exit the body, bypassing the bladder.

Resources

American Urological Association

Lightner D.J., et al.

“Diagnosis and Treatment of Non-Neurogenic Overactive Bladder (OAB) in Adults: an AUA/SUFU Guideline (2019)”

(Guideline published: 2012; Amended in 2014 and 2019)

https://www.auanet.org/guidelines/guidelines/overactive-bladder-(oab)-guideline#x2904

Healthline.com

Ellis, Mary Ellen

“What Are the Best Medications for an Overactive Bladder?”

(Updated: September 2, 2018)

https://www.healthline.com/health/overactive-bladder/medications-for-overactive-bladder

Healthline Editorial Team

“Botox for Overactive Bladder”

(Updated: November 29, 2017)

https://www.healthline.com/health/overactive-bladder-botox

Wallace, Ryan

“11 Foods to Avoid if You Have OAB”

(September 28, 2017)

https://www.healthline.com/health/11-foods-to-avoid-if-you-have-oab

LiveScience.com

“How Much Urine Can a Healthy Bladder Hold?”

(December 4, 2012)

https://www.livescience.com/32330-how-much-urine-can-a-healthy-bladder-hold.html

MedlinePlus.gov

“Self catheterization – female”(Last reviewed: January 10, 2021)

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000144.htm

“Self catheterization – male”

(Last reviewed: January 10, 2021)

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/patientinstructions/000143.htm

“Urine culture”

(Last reviewed: October 10, 2020)

https://medlineplus.gov/ency/article/003751.htm

Medscape

Ellsworth, Pamela I., MD

“Overactive Bladder Treatment & Management”

(Updated: January 21, 2021)

https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/459340-treatment#d11

Rao, Pravin K., MD

“Augmentation Cystoplasty”

(Updated: March 2, 2021)

https://emedicine.medscape.com/article/443916-overview

Merck Manual – Consumer Version

Chung, Paul H., MD

“Urinalysis and Urine Culture”

(Content last modified: May 2020)

https://www.merckmanuals.com/home/kidney-and-urinary-tract-disorders/diagnosis-of-kidney-and-urinary-tract-disorders/urinalysis-and-urine-culture

National Association for Continence

“Ask The Expert: Can Kegels Really Help My OAB Symptoms?”

https://www.nafc.org/bhealth-blog/ask-the-expert-can-pelvic-floor-exercises-really-help-my-oab-symptoms

“Overactive Bladder”

https://www.nafc.org/overactive-bladder

National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases

“Definition & Facts of Urinary Retention”

(Last reviewed: December 2019)

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/urinary-retention/definition-facts

“Urinary diversion”

(Last reviewed: June 2020)

https://www.niddk.nih.gov/health-information/urologic-diseases/urinary-diversion

Urology Care Foundation

“It’s About Time . . . And It’s About You: It’s Time to Talk About Overactive Bladder”

(2021)

https://www.urologyhealth.org/educational-resources/overactive-bladder

“What is Urinary Diversion?”

https://www.urologyhealth.org/urology-a-z/u/urinary-diversion

VoicesForPFD.org (American Urogynecologic Society)

“Botox® Injections to Improve Bladder Control”

(2018)

https://www.voicesforpfd.org/assets/2/6/Botox.pdf

WebMD

Brown, Steven

“What Is a Post-Void Residual Urine Test?”

(Medically reviewed: February 10, 2020)

https://www.webmd.com/urinary-incontinence-oab/post-void-residual-test

Watson, Stephanie

“What Is Electrical Stimulation for Overactive Bladder?”

(Medically reviewed: February 11, 2020)

https://www.webmd.com/urinary-incontinence-oab/overactive-bladder-electrical-stimulation